12 Attributes of a Great Leader

I believe that most managers want to be great managers. In fact, many aspire to transcend management and to be deemed leaders. While there are countless books on the topic, sometimes they are too much theory and not enough practice, to be relevant and applicable. One of the main roles of a leader is to teach; through actions of commission, actions of omission, and through a thoughtful dialogue. The goal of this series is to share what I believe are the hallmarks of great management.

In High Output Management, Andy Grove explores why, at times, an individual is not able to achieve their potential in a job. He simplifies it to one of 2 reasons: 1) they are incapable, or 2) they are not motivated. In either case, it's the responsibility of the manager to assess and remediate the situation. This is not comfortable, nor easy. Hence, this is why great leadership is difficult.

I will focus on what I think are the 12 defining attributes of a great leader:

1) Team builder- assembling and motivating teams.

2) Running teams- a disciplined management system, based on thoughtful planning.

3) Expectations, Accountability, and Empowerment - the #1 issue I see is here.

4) Being on offense, not defense- leading instead of reacting.

5) Engagement and influence- creating informal influence broadly.

6) Operational rigor- managing the details, without micro-managing.

7) Clear and candid communication - never leaving a gray area.

8) Training- a critical role of a manager.

9) Mental toughness- never talked about enough, yet many managers fail due to this aspect alone.

10) Strategic thinking- having a point of view, differentiated and right.

11) Obsessing over clients- knowing who pays the bills and applying it to every decision.

12) Positive attitude- Motivating by example.

I'll cover each topic via blog and/or podcast.

***

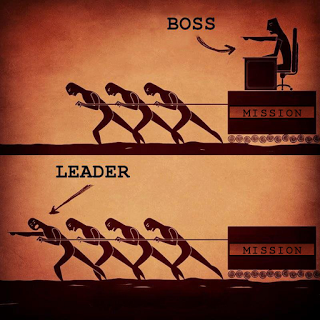

2) Running teams-

The hardest thing for a new manager/leader to adjust to is being the pace setter. Once you assume the role of a leader, your job is to be on offense, not defense. I see even the greatest individual contributors struggle with this at times, because their success has been defined by doing everything that is asked of them. However, once you assume the manager role, you must become the one setting the direction and sparking activity. And, it can't just be activity for activity sake; it has to be thoughtful, pointed, and focused. This is the notion of a thoughtful management system.

In this podcast, I am joined by a great leader, Derek Schoettle, who was the CEO of Cloudant, before joining IBM via acquisition. We discuss how effective managers run teams, set pace, and foster open communication. 3 major topics are covered:

1) Committing to a course: No sudden, jerky movements and how to establish consistency in communication patterns.

2) The Rockefeller Habits: Set priorities (1-5), manage key metrics/data, and establish a rhythm.

3) Conducting 1-on-1's: Using formal and informal approaches to communicate for impact.

I hope you enjoy the podcast.

***

5) Engagement and influence-

"Great leaders are relaxed when the team is stressed, and stressed when the team is relaxed."

I had a chance to talk with Jerome Selva about Engagement and Influence recently.

Podcast here.

We discuss:

- Informal Influence

- Getting comfortable in your own skin

- Tools for informal influence (blogs, videos, etc.)

- Looking outside your defined scope

- Emotional intelligence

In addition, Jerome shared the following for further reading:

Travis Bradberry and Jean Greaves — "Emotional Intelligence 2.0"

Emily Sterrett — “The Manager’s Pocket Guide to Emotional Intelligence”

Daniel Goleman "What makes a leader"

HBR article: https://hbr.org/2014/03/spotlight-on-thriving-at-the-top

EI test: http://www.ihhp.com/free-eq-quiz/

***

7) Clear and candid communication -

I tend to say whatever is on my mind, as succinctly as possible. I believe it provides clarity (even if it’s not agreed with) and clarity leads to speed. Hence, I’ve always leaned towards saying exactly what I am thinking. I’ve had more than one person tell me, “you say the things that other people are thinking.”.

Now, that’s my style. It doesn’t mean it’s the right style or the only style. Everyone is different and should communicate in a manner that fits their style. That being said, I think one hallmark of leadership and management is being able to have the candid conversations and if necessary, delivering the uncomfortable truth.

In this podcast, I am joined by a colleague, Ritika Gunnar, to discuss the topic of Candid Communication as a manager and leader. Our conversation focuses in 3 areas:

1) Sharpening contradictions: the best managers identify disagreement in their team and tease it out. They know that letting it persist can create an unhealthy culture. It’s much better to get it on the table, even if it leads to a difficult discussion, than to let it lie in the background.

2) Don’t let problems linger: if you have a challenge with someone or something, speak up…put it on the table. If you let it linger silently, frustration and anxiety build and the trust amongst a team deteriorates over time.

3) Giving feedback: for many managers, it is very hard to give candid feedback, especially when it is negative or potentially confrontational. I believe that at their core, everyone wants to know the truth and where they stand. So, we discuss some techniques for how to deliver the harder messages. Your teams will thank you for it (sometimes many years down the road).

I hope you enjoy the podcast.

"In classical times, when Cicero had finished speaking, the people said, 'How well he spoke', but when Demosthenes had finished speaking, they said, 'Let us march'"- Adlai Stevenson